Monday, 2 November 2009

Early Sunday morning I got up, showered, and fed myself breakfast. Katy was up soon thereafter and offered me a cup of tea. The kids and Karl were still in bed, so I thanked her and asked her to extend my thanks to the rest of the family for the wonderful hospitality I had been shown over the past two days. With my bags in hand, I descended the stairs and caught a cab. The driver knew the destination when I gave him the street address—a novelty here in Cairo—and since it was early morning and traffic was light, I reached Simon Bolivar Square in no time.

I wasn’t sure exactly where the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) building was, but just as I was about to go looking, a tour bus pulled up and parked on a side street. The driver climbed down and I asked him if he were headed to the Fayyoum today. He said yes and please, would I like to board. Grateful for the chance to get my weighty backpack off my shoulder I went up the steps and dropped said bag onto a seat, taking my place next to it. While I waited for the rest of the group, I cracked open my Blue Guide to Egypt and read up on the Fayyoum.

The Fayyoum is a geographical feature located south and slightly west of Cairo. Sort of an oasis, it is a fertile area created by an offshoot of the Nile, which flows into a low area and creates a lake, called Qarun, which has no outlet. Since ancient times, it has been the site of intensive agricultural activity; evidence of farming dates back 7000 years here. Beginning in the time of the Ptolemies, the Fayyoum was developed for large-scale agricultural production, mainly wheat and olives, using the waters of the Nile to irrigate the land. In the days of the Roman Empire, the Fayyoum provided Rome with much of the wheat it needed to feed its population. Even today, agriculture is the primary activity here, although a huge industrial park is currently under construction on land that is unfit for farming.

I was interested in this area because, according to my research on Arabic block printing, many of the examples of this craft originated in the Fayyoum. Apaprently, in the late nineteenth century, as a consequence of renewed interest in the ancient Middle East generated by Napoleon’s scientific expedition in Egypt, Europeans flocked to this part of the world. Between the end of the French military adventure in Egypt (1801) and the second decade of the twentieth century, many of the major discoveries relating to Pharaonic Egypt took place, including King Tut’s tomb. Europeans were so keen to lay hands on anything bearing even a whiff of antiquity that they created a market for such things among the population. Thus it was, apparently, that some of the block prints ended up in European libraries and museums.

At the time in the Fayyoum, ancient mud brick structures, long collapsed and fallen into disuse, were being harvested for their potential as fertilizer. Sort of Biblical: “from dust to dust,” in a way. Occasionally, mixed in with the rubble, were fragments of manuscripts, which people understood were worth money. There were these nutty Europeans in Cairo who would actually pay money for this junk! Hey, beats farming for a living!

At least that’s my imaginary reconstruction of the scenario. In any case, the sources I read say that something like this did occur in the Fayyoum and I wanted to see the locus first-hand. Karanis, the archaeological site I was visiting, had been the site of mud brick (known in Arabic as “sebakh”) removal on an industrial scale. The archaeologist working on the site was going to be our tour guide and I wanted to hear if she had run across any block printing fragments.

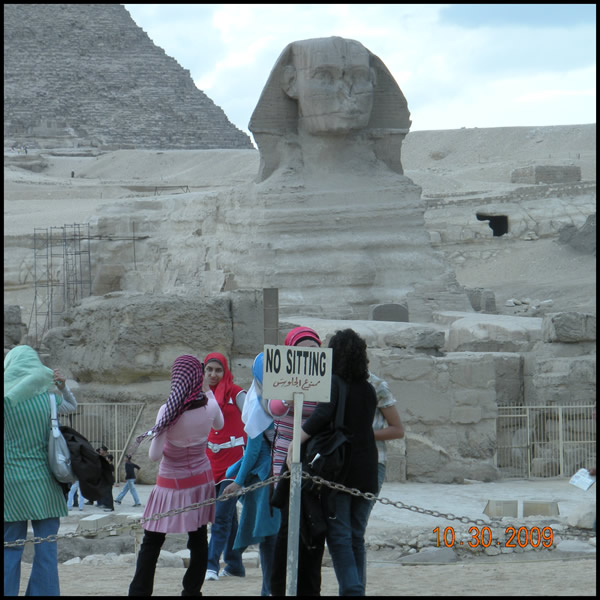

The rest of the group gradually appeared and boarded the bus. At 8 AM sharp, Mary Sadek, the person from ARCE who had organized the trip, announced that all were present and we set off. Our route took us through Giza, past the Pyramids rising majestically from their hilltop abode, and south along the edge of the desert. The road was a four-lane, heavy with commercial traffic, but not congested. There were a couple of traffic control stations where cops were checking for valid licenses and bills of lading, but the eighty kilometer trip took less than two hours in all. Karanis lies at the northeast extreme of the Fayyoum and so is closest to Cairo of all the sites and settlements there.

While we were underway, Mary distributed small battery powered electronic devices containing an ear piece and a receiver that clipped on a belt or backpack strap. The purpose of these units became clear when we arrived at the dig site. Dr. Willeke Wendrich, the archeologist in charge of the Karanis excavation, met us in a shady area at the foot of the tel (the hill created by layers of successive settlements being built atop one another over hundreds (in some cases thousands) of years—Tel Aviv is perhaps the most famous “tel”) and donned a similar unit which had a microphone attached. In a large group, she could thus make herself heard without having to shout. Brilliant.

Dr. Wendrich excused herself at this point and turned the tour over to one of her graduate students, Bethany, who led us northeast to the next point of interest, the “South Temple,” which was built of stone and has therefore withstood the ravages of time better than the mud brick dwellings of the town. She explained the structure and let us clamber around for a bit. We got to see the altar and the niche adjacent to it where, in its heyday, a mummified crocodile reposed. (One of the most important cities in ancient Fayyoum was called Crocodilopolis, and the crocodile was deified in the Fayyoum).

From there we walked to what had been the center of the ancient town. It was from here, Bethany explained, that most of the mud brick rubble had been excavated. What came as a shock was her description of the operation. I had been under the impression that the quarrying had been done by local farmers, using manual labor and donkeys to carry the material to their fields, but our guide explained that here, in Karanis, the Egyptian government had given a license to an Italian company to excavate the rubble and they had used machinery, steam shovels and the like, and had laid two railways—the sort used in mining—onto the tel to carry away the material. The University of Michigan archaeologists had to negotiate with the company to get them to stop, promising to deliver the material that the archaeologists excavated to the company.

Our last stop was a location on the northeast edge of the tel, where the remains of a dwelling and another granary had been uncovered. The archaeologists were very excited because evidence of decoration in the house, consisting of plaster painted with colors not previously seen here, had been found the previous day.

Our bus was waiting for us a short distance away, and we boarded it for our short trip to the new dig house. Once we arrived, we sat down to lunch in the dining room. The house was a single story of concrete, with several work rooms on the ground floor and a rooftop patio and three offices for the archaeologist and her assistants. Dr. Wendrich runs an archaeological field school here and there were several students and supervisors working at various tasks: compiling field notes, conserving artifacts, cataloguing pottery shards, and the like. After lunch, Dr. Wendrich gave a brief slide presentation on the Karanis project and answered questions. We had a brief tour of the building, a chance to speak with the archaeologists about different aspects of their work, and then prepared to depart. I spoke with Dr. Wendrich about the lack of Islamic remains and told her what I was looking for. She confirmed what Bethany had told me about the absence of Islamic evidence at Karanis, but said that there was a French excavation at another site where Islamic remains were found. I will have to find out where that is…

After thanking our hosts, we re-boarded the bus and settled back for the return trip to Cairo. That journey concluded without incident and I headed off for the train station and my return trip to Alexandria. I spent almost the entire ride catching up with my blog posts; so intent was I on that task that I nearly missed my station. However, I managed to cram everything into my backpack and alight before the departure whistle sounded. A quick taxi ride home and into bed. Tomorrow, I begin my collection development workshops and I’m a bit apprehensive about them.