Friday, 18 September 2009 A night of broken sleep: wide awake at 1 AM; asleep again until 4 when, over a loudspeaker, the local mosque (a literal stone’s throw away) issues the call to begin the day of fasting; a couple of aspirin for a headache and then awakened at 7 by the alarm. I get my bearings and stumble out to look at the new day. My apartment faces west and the big living room window has a balcony outside it. I open the thick thermal curtain and see that the sun is up and the sky is hazy. I open the balcony door and step out. The air is not very cool, but there is a soft morning breeze and I decide to throw both the heavy curtain and the lighter ones back, open both doors and let some fresh air in. I don’t know how long this apartment has stood vacant, but since the last Fulbrighter to inhabit it left last June (I’m guessing), the air is a bit stale. It’s apparent that the apartment has undergone some remodeling recently and I begin to take a closer look. The wooden floor is new and pretty rough in places, even through the finish. In the kitchen, the cabinets look new, too, but the dishes in them are covered with dust, as are the counters… The cabinets still have empty boxes that contained the tableware, glasses and cooking utensils. I find a package of garbage bags and start packing up stuff to be discarded. I make myself a cup of Nescafe (the only kind Ibrahim bought yesterday; at least it’s hot and tastes sort of like coffee) and continue poking around and assessing my situation. I realize suddenly that it’s awfully quiet outside. There’s no traffic noise. I realize that Friday is the beginning of the Egyptian weekend. A quick survey of the street below reveals that the steel doors over the shop fronts are down: no shopping today. Okay, I’ll just putter around for now and wander out later when it’s cooler. Still don’t have internet connection; one of the tasks Ibrahim had yesterday was to contact the internet service provider—Etisalat—and get the DSL line straightened out. He had told me that it might be a day or two yet and that obviously didn’t include today. My machine is getting the wireless signal from the router, but the signal apparently isn’t getting back to the company. Being out of touch is beginning to be a concern because I don’t know what’s in my e-mail inbox. The TV is also out; it’s a satellite system and I’m clueless as to which box is supposed to control the whole thing. Thankfully, I brought my shortwave set and can get FM Egyptian broadcasts as well as BBC and some German and French stuff, so I feel connected in some way. I wander around the apartment not wanting to go outside into the heat and with no purpose in mind. I finally get the TV working. With a limited number of buttons and possible combinations, it was only a matter of time. Lots of Koran reading today; lots of Jimmy Swaggarts and Oral Roberts types in Arab garb and speaking Arabic, but working toward a similar end. There being no towels to be found, I finally decide that air drying is an acceptable alternative, so into the shower (nice pressure; lots of hot water). With an air conditioning unit on, it doesn’t take too long for the water to evaporate and I get dressed to make my first foray into the city. Ibrahim had told me that a major shopping center (I never thought I’d be glad to hear there’s a mall nearby!) was just a few blocks away and I wanted to see just how far. I walked east on my street until it angled into a larger thoroughfare. There were a few people out and a few lighted shops, but the way was inhabited mostly by stray cats and an orchestra of offensive odors: garbage, oil, unburned gasoline, sweat and all sorts of other gook. A large puddle shimmered in Technicolor under the dim street lights. There was a streetcar line running down the center of this street, bounded on each side by a low masonry wall. When there was a break in the wall at an intersection, I turned back and walked alongside the tracks until I reached an intersection that took me past my street again. Kept on walking northeast, toward the Corniche, and on the lookout for a decent restaurant. I had Dr. al-Wostawy’s warning about bad restaurants in mind, but after a mile or so, I decided that I had tried hard enough. Fortunately, I spied a hotel and restaurant—the San Giovanni—that Ibrahim had mentioned, so I strolled in. A dark-haired young woman in an elegant pants suit ushered me up a short flight of stairs to a seating area containing tables covered with checkerboard cloths. An Egyptian of African descent guided me to a table next to a glass wall looking out over a small cove with waves splashing against a jetty below. I ordered a Stella, an appetizer and a chicken and macaroni dish. I spent a pleasant hour eating and watching people and their children breaking their fasts along the sea and then walked back to the apartment. I sat down to write up the day’s events when, to my surprise, the computer told me that I had an internet link. What joy! I quickly logged on, cleaned out my inbox and managed to post two blog entries before the link went down. I should have my own link in a day or two, but now, even if that doesn’t get seen to, I know I’ll at least have SOME SORT of contact. I probably won’t be able to Skype or do elaborate stuff—I keep getting disconnected at inconvenient times—but at least I have a window of sorts. Now, if only the stores are open tomorrow…

Posts tagged ‘egypt’

Alexandria- Day One

Off to Alexandria

Thursday 17 September 2009

Up at seven to make myself presentable for the people at Bibliotheca Alexandrina later today. I get a quick breakfast and when I get back to my room, I realize that I haven’t been drinking enough water. It’s hard to find bottled water in the stores when most people are fasting. They are careful to avoid being around food and drink if at all possible and I read in the paper today that people (I assume Muslim people, but who knows?) who eat in public during the day in the month of Ramadan are liable to arrest. And that’s Egyptian law, not Muslim law. I order bottled water from room service and drink it while I finish packing. A little after nine, I drag my stuff downstairs and tell the desk I’m checking out. I am asked to wait while they check the room. Really? I guess they’ve lost too many towels or pillows…

While I wait, I get talking to a woman who tells me that she’s visiting Egypt for the first time in nearly twenty years. She was born in Egypt but married an Australian and has lived in the West for most of her adult life. Her children gave her a tour package for Mother’s Day and she decided to come back with one of her daughters. She shared some tips about dealing with taxi drivers and other bits of info about Egypt. I catch sight of Ibrahim waiting patiently on the street, so I say goodbye and take my stuff outside. We stuff everything into the trunk and the back seat and set off. Alexandria is about 200 miles away and it takes us some 2 ½ hours to get there.

It takes us about half an hour to clear the congestion of Cairo; my mantra about that issue should be well absorbed by now, so I won’t dwell upon it longer. After a while, we reach the ring road and head off toward the west, and then north. We can drive at the speed limit (100 kph) most of the time and the fact that we are now some distance from the Nile is apparent in the drier landscape. The median of the six-lane we’re traveling on is planted with a variety of trees and shrubs; some seem to be faring better than others, depending on how close they are to settlements and how much water they get. Ibrahim tells me that the olive trees planted in the median may be harvested by the locals; the government apparently permits this as a way of assuring (in some way) that the trees are given a minimum of care.

Even on the highway, one has to be careful of pedestrians crossing the road. Imagine driving on I-80 and having to watch for men and women, kids in tow skipping their way through rush hour traffic. I wonder what the yearly death toll for these people is… Every so often there are formal or informal rest areas. Some are obviously the result of individual enterprise; others bear the distinct mark of corporate interest: better, cleaner, more permanent facilities and services, paved parking, etc., but drivers seem to stop at both kinds in equal measure, depending, no doubt, on their financial circumstances. Donkey carts and hitchhikers appear occasionally on the shoulders of the way.

We enter a region where the road is lined on either side with walled compounds of varying size and signs indicating that they are farms. I ask Ibrahim about this and he says that these are the result of government investment in agricultural development. This part of Egypt, called the Wadi Natrun, is a traditional Coptic area and some years ago, it was discovered that there are vast water resources under the earth here. About 150 meters below the surface is a major fresh water aquifer and the government decided that agriculture on a scale larger than the traditional farm would be possible in the area. Hence, the land was acquired and sold to people who wanted to farm it. The plots are of different sizes—five, ten, or twenty “feddan”—the Egyptian measure for land area (don’t know the exact equivalent in acres, but my guess is than a feddan is about a half acre, maybe…). Most of the plots are walled with brick and concrete, with elaborate gateways bearing mottos or the name of the farm. Row crops such as tomatoes, peppers and other vegetables are grown as well as olives and citrus, bananas, too. This isn’t the Oklahoma land rush where anyone can take part; one obviously needs serious capital behind them to undertake the development of the land. Ibrahim told me that he had some land near El-Alamein (yes, the WWII battle site) and wanted to do some farming on it. 150,000 Egyptian pounds to drill a 150 meter well, buy the pump, pipe and compressor needed to get the water to the surface. He said “no thanks,” and walked away.

Unfortunately, it appears that the development pattern here is taking the same form as in the States. Modern shopping malls and housing developments are planned, too, creating more sprawl and congestion for the future. Billboards advertising these ventures dot the highway for miles. Mosques, too, appear at frequent intervals. One particular building struck me because of the seemingly odd construction of its minaret and the two-tone color scheme in the tiles covering it. After a seeing a few, it struck me that the mosques were pretty cookie-cutter and I concluded that somebody might have gotten the mosque franchise for this route. No doubt the reason for the frequency of mosques is the need for observant travelers (long-distance truckers in particular) to have convenient prayer stops when the appointed prayer times roll around. After a couple of hours we leave the highway; at the “toll booth” Ibrahim rolls down the window and simply tells the toll taker that he’s on “official business” and we roll right through. I’ll have to try that the next time I drive to Chicago.

We enter an area where reed marshes stretch away on either side of the road. Ibrahim says that these are salt marches, low areas where water lies year round. [It’s actually the edge of Lake Maryut, an ancient lake now much smaller than it once was because of infilling and other human activity.] I see fishing nets hanging to dry in a couple of places. Shortly after this, Alexandria pops up on the horizon. The city hugs the shoreline for about twenty miles just west of the Nile delta. The traffic here seems as bad as Cairo’s, if not worse since the density of building is higher along the coast and because the main east-west route, the Corniche (coast road) is the only way to get through the city. We drive for several miles along this road, with the usual pedestrians playing chicken with cars zipping along at speed. We find the street (Ibrahim seems to navigate by landmarks rather than street signs (I STILL can’t always locate them when I ride in a car or bus and I think that they are probably not posted uniformly) and turn off the Corniche.

The street we’re on takes us past the University of Alexandria’s College of Agriculture campus and we turn left onto an even narrower street. A hundred yards along that, we turn left again into a still narrower road and park tight up against a wall in front of a row of apartment houses. We’ve reached our destination. A young man comes up, Ibrahim apparently knows him, and together we unload the car. Ibrahim leads me up a set of steps lined with two foot high palms in pots into a dark and elaborate foyer. We drop the bags and walk to an office where I’m introduced to a Mr. Magid. I can’t make out whether he’s the owner, or the manager. In any case, we do the introductions and exchange bits of necessary information and then board the elevator for the ride to the sixth floor.

We emerge into a dim hallway and Mr. Magid opens a door. We step into a foyer with wooden floors and walls painted in an off-white. Mr. Magid turns on the light and I get my first look at my digs for the next four months. My first impression is “holy sh—t.” The place is huge: to the right of the entrance is a dining/living area at least twenty feet long and fifteen wide; the floors are narrow wood strips arranged in a herringbone pattern with a narrow border of strips laid perpendicularly to the walls and separated from the herringbone pattern by an inlay of darker wood strips in a geometric design. The furniture is a mixture of styles and my first impression is Queen Victoria meets Louis XIV on LSD meets New Orleans bordello. The dining table is heavy and dark with six wooden chairs around it. It sits on an area rug with a leaf pattern in it. The living area has a huge overstuffed couch with gold colored cushions and pillows and two matching chairs facing it. A blonde wood table with lion claw feet sits in the middle of the room. The table also rests on an area rug, that one with a modern geometric pattern in it.

At the far end of the room is a floor to ceiling, wall-to-wall window covered with a blackout curtain. Heavy, fringy, lacy curtains hang at either end. After taking this in, I get a quick tour of the rest from Mr. Magid. There is the kitchen, long and narrow with modern appliances, counter space, cabinets, stove, refrigerator and a water purifier sitting next to the sink. Mr. Magid demonstrates its use. A short hallway leads from the kitchen to the bedrooms. The first is obviously for the parents, a queen-size bed, vanity and wardrobe in an atrocious modern style, looking like it was put together by a committee of eager designers each determined to have his or her idea included. Blonde wood with chrome metal, fabric, and rope elements. The vanity is cutesy but small and unobtrusive; the wardrobe is built in and takes up most of one wall. Lots of storage space and that’s all I care about. Down the hall is a second bedroom, more heavy dark furniture, two matching beds with Minne Mouse comforters on them. “My beautiful daughter” stenciled on both. No favoritism here. Another huge wardrobe. At the end of the hall is the TV room, two couches against two walls, a coffee table in the center. Past this is another small space with a tiled floor and three framed pictures. Around the corner and we’re back in the foyer. A second toilet is on the left. Too much space for me.

Ibrahim reminds me that Sohair al-Wastawy, the Director of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina is expecting me, so I throw on a fresh shirt and we’re off. Back down the Corniche to the library, a couple of miles away. Ibrahim is uncertain where to drop me, so he’s on the cell phone trying to get directions. He has trouble reaching Dr. al-Wostawy and after circling the block in a rather convoluted manner, he finally pulls up to the curb outside the library and we simply wait to see the director waving from her office balcony. I wave back and head for the entrance. Ibrahim drives off to take care of apartment stuff; we agree that I will call him when I’m done and he’ll pick me up and take me back to the apartment.

I meet Dr. Wostawy’s assistant, Hind, at the VIP entrance (wow) and she escorts me inside. We go to the director’s office and get acquainted for a few minutes. She’s obviously busy so I don’t take a long time and when we part, Hind takes me back downstairs to meet Ingy (pronounced Injee), who has been detailed to give me a VIP tour (wow, again). Ingy is very knowledgeable, full of statistics and figures about the founding and construction of the library, but she shows me lots of interesting things in the short time we have. Her English is impeccable and I’m glad that I don’t have to struggle with Arabic. I’ve arrived on the eve of the Eid at the end of Ramadan and the library is closing at 2:30, so we skip over a lot of the details; some of the things I’m supposed to see are already closed.

When she’s finished her task, she has me escorted back upstairs to another librarian, Dahlia, who is in charge of library training and who has been asked to show me some of the four specialized libraries. On the way she explains the organizational principle of the building and its various sections. I am particularly taken with the fact that each section has its own reference desk staffed by librarians who specialize in that field. In addition, there is a reference desk located on each of the seven reading room levels. The newest addition to the library is a supercomputer that serves as an archive for the internet. It’s the first one of its kind in the world to be located in a public area (although it’s behind glass, one can see all the components: rack after rack of processing units with incredible calculating speed and something like 30 terraflops of memory. How much is that?! It takes snapshots of the web every ninety days; a monitor shows random samples of what’s archived. There is also a newly installed video and image archive and more stuff coming. We visit the children’s and young people’s libraries, the only sections that actually lend materials. Everyone who uses the library must become a “member,” although it is possible to become a one-day member. Rates are scaled depending on how old you are and how long your membership is.

Closing time has come and gone and I see that Dahlia is anxious to get home. I thank her and wish her a happy holiday. She drops me at the entrance and I call Ibrahim to tell him I’m free. When he picks me up, he tells me that Dr. al-Wostawy has been trying to contact me. I apparently didn’t hear my phone. Ibrahim calls her and hands me his phone. She has some materials she wants to give me and tells me that one of her colleagues is looking for me near the entrance. I hop out of the car and run back to the entrance where I find Amr holding a plastic bag full of books, pamphlets and a list of acceptable restaurants in Alexandria. Dr. al-Wostawy had told me to be careful. “There are a lot of dirty restaurants in Alexandria and I don’t want you to get sick,” she said.

We drive back to the apartment and Ibrahim pulls a couple of plastic bags full of groceries out of the trunk. There’s milk (oh, joy!), coffee, bananas, bread, cheese and other essentials. I offer to pay him, but he refuses. “A gift from the Fulbright Program,” he replies. Does the US Govt. know how generous these people are being? He wishes me a pleasant stay in Alexandria and we say goodbye.”Call my cell if you need anything,” he calls as he boards the elevator. “Right,” I say. As if I’d ask him to drive all the way from Cairo to deliver it. Way beyond the call of duty. Finally, I’m on my own and I proceed to take a closer look at the apartment. What unpleasant surprises await me now that I have to rely on my own wits?

I start unpacking, slowly, deciding what should go where and hoping I’ll remember where I put it when I need it. I could use some more clothes hangers, first of all, and I make a mental note to start a list. The big bag gets emptied first and then stowed away. I grab the package of pita bread Ibrahim left and slap some cheese on a couple of pieces. I haven’t eaten since breakfast. I start poking around in the wardrobes and drawers. Where are the sheets and towels? Oh, one pair—no, ONE sheet. Oh, one’s already on the bed. The one I find is a bit worn and too small for the bed. No others? Nope. Oh, well. I’ll make do until I can buy some proper ones. Gee, I’d really like shower; WHERE are the towels? A thorough search reveals none. Oh, great. Guess I’ll have to air dry for now. Another item for the list. I’m getting tired and decide to call it a day. I figure that I can begin stocking up on things I need tomorrow. I put the frazzled sheet on the bed and change out the half-ton comforter for a lighter one. There is a spanking new air conditioning unit mounted in the bedroom wall; I set it on “economy” and drift off to sleep.

The Missing Day

[Chronologically, this post should be read after the first one] Tuesday morning. Awake after about four hours of sleep. Morning ablutions and then down to breakfast on the hotel mezzanine. An indifferent selection of pastries, cold cereal, breads of various kinds, jams and jellies, orange juice (thankfully), cold meats and cheese. Even a few pieces of sushi—rice and cucumber rolled in dried seaweed—but I pass on that. I hang out at the hotel for a while, read the English language newspaper that has been dropped outside my door—the Egyptian Mail (“The Middle East’s oldest English language weekly” says the caption under the paper’s name…) and around 10 head out to locate the Fulbright Center so I know how to orient myself for Wednesday’s official visit. The sun is bright and glaring in the smog as I walk to the corner where two taxi drivers ask if I need their service. I decline and turn right onto Amer Street. Half a block down is an HSBC bank branch where I enter to change some money. There is a Cairo cop outside the door, dressed in the standard white uniform with black boots, belt and beret. He glances up at me: “obviously an American,” he thinks; “no trouble.” Inside the door is a bank security person whom I greet in Arabic and he responds. Up a circular staircase to the second floor where two guys at a desk hand me a chit with the number 22 printed on it. There is a counter with three bank employees behind it and about eight or ten men sitting in chairs, waiting. A little illuminated sign tells me that number 16 is now being served, so I figure I have to wait a bit. I find a seat and watch the proceedings. Many of those waiting seem to know each other and quiet conversations are being held here and there. A young woman in dark clothing with her hair covered in a black cloth comes out from an office area and begins mopping the floor at the top of the stairs, She then works her way down the staircase. “Number 18” calls out the electronic female voice. There’s a minor disturbance at the top of the stairs, a verbal altercation between a customer and one of the bank employees. Everyone turns to watch and when the situation calms down, everyone has an opinion about what happened. Laughter seems to be the most common reaction. I’m glad that I decided to take care of the currency conversion early; the pace of service is agonizingly slow. Some customers have to return to the counter twice to complete their business. “Twenty.” Only one person in front of me now. It’s cool and pleasant in the bank and I’m in no hurry to face the heat of the street. Finally, “twenty-two” and I go and take care of my business. I pull out my American currency and the teller goes on auto-pilot. He pulls a form out of his desk, notes the amount I hand him, checks the bills to make sure they’re not counterfeit and shows me where to sign my name on the form. SO much easier than the States where banks treat customers who want to exchange currency like criminals: “Where’s your passport? Do you have an account here? No, we don’t take travelers’ checks.” No wonder the world thinks we’re arrogant. I thank the teller and take the stairs back down and out to the street. Across the way I notice an official-looking building with two more cops outside the gate. Thinking that that must be the Fulbright office, I cross over and immediately see lettering on the white wall identifying the place as the Center for German Studies in Cairo. An interesting discovery, but not what I’m looking for. I approach the two cops who are speaking with a traditionally dressed woman. All look up as I come near; I remove my sunglasses—a courtesy to people in the Middle East, who like to look you in the eye—and say hello in Arabic. I then ask for the street address I want. They point behind me and tell me to follow a street that runs perpendicular to the one we’re standing on. “On the right about halfway down,” one of the cops says. I thank them all and walk away. I find the building where I was told I would. It’s tucked away behind a fence and between two taller buildings. I make a mental note of landmarks and begin to walk back to the hotel. Just then my driver Ibrahim appears from behind the fence. We greet each other and shake hands. He asks if I’m coming in; I reply no, I’m just making sure where I need to go tomorrow. He tells me he’ll see me on Thursday for our drive to Alexandria. I say I’m looking forward to it and we say goodbye. Just before noon I’m back on the street corner ready to do business with the taxi drivers. There are two and the one who speaks first gets my business. He asks where I want to go and I give him the address. The American Embassy in the Garden City section of Cairo. I give him the street address. We hop in; it’s an old car, black and white, a Japanese product showing lots of urban wear and tear. Although there’s a meter, it isn’t turned on. We’ve been told that this is common practice and therefore we should negotiate a fare before we get in. I want to be on time for my appointment, so I skip that detail. We cross the river going east with the driver pointing out landmarks and making small talk. Very small, since my Arabic is rudimentary at best. We get to Garden City in about fifteen minutes but he obviously doesn’t know the area because he can’t find the street. He asks a couple of people who don’t know either but finally a cop points him in the right direction. He finds the street (I can’t make out the street sign amidst all the business signs on the building walls) and stops the car. The one landmark I have been told to look for—an Avis sign—is visible and I just hope it’s the RIGHT Avis sign; I’m sure there’s more than one in Cairo… “How much?” I ask. “Thirty Guineas” (Egyptian Pounds) he responds. About six bucks American; I hand him a 100 Egyptian pound note and get 50 in change. Oh yeah. These guys don’t carry small bills; we were told to expect that, so I walk away about ten dollars wiser, I hope. Our meeting is supposed to begin at 12:30 PM; I have several minutes to wait, but I begin to get a bit nervous when no one else seems to be stopping under the Avis sign. Just as I’m about to ask someone if that is indeed the American embassy just behind the barriers in the street, I see two sort-of-familiar faces. They walk toward the barrier and I overhear them asking about the Fulbright meeting. Okay. I feel better now. I run up and say “hello.” They remember me and now they look even more familiar. We head to the embassy gate and meet up with everyone else. The afternoon is spent getting oriented by various people. The American ambassador, a career foreign service officer (and NOT, thank goodness, a wealthy political donor) who has a long record of service in the Middle East, and was appointed to the post last Spring. Good move, Barack. Four hours later, we’re done and climb aboard a bus for a celebratory “Iftar,” the ceremonial fast-breaking meal taken after the sun sets each day during Ramadan. It has been arranged that we enjoy this feast at a restaurant in the citadel of Salah al-Din, the Ayyubid (Kurdish/Turkish) Muslim leader who is most famous for kicking the Christians out of Jerusalem in 1187 AD. We head east through the slums on the city’s eastern edge toward the Muqattam Hills, the highest geographical feature, anywhere near Cairo, composed of limestone and perfect for quarrying building stone.  The sun is about a hand’s width above the horizon when we arrive, and we stand at a railing overlooking the Cairo skyline and the setting sun through a thick veil of smog and dust. The lights come on as we stand and talk; the wind freshens from the south and whips our hair. Along a wide esplanade paved with stone, waiters are busy laying tablecloths on tables, long ones to hold the buffet dishes and round ones where groups of six will sit and eat. The sun is still above the horizon, only barely, when we are called to the buffet line. We claim chairs for ourselves, pairing off and grouping up, and then load our plates. There are dishes that I recognize and dishes I don’t. Mezzeh, the Arabic antipasto is there: hummus (chickpeas ground finely and mixed with cumin, garlic and sesame sauce, tabbouleh (a salad made with cold cooked wheat kernels, onions, tomatoes and parsley) baba ghanoush (roasted mashed eggplant also mixed with garlic, sesame sauce and other spices), grape leaves rolled around cooked and spiced rice), kibbeh (ground lamb rolled in little sausage shapes and hiding pine nuts in the middle; these are grilled), and triangular puff pastries filled with mashed potatoes and then baked. All this is best eaten with generous amounts of pita bread—a pile of frisbee-shaped loaves sits in the middle of each table. It’s apparently traditional to begin the meal with a soup, and two are on offer. One is a vegetable soup and the other a cream type. There are rice dishes, more eggplant, a casserole that reminds me of Greek moussaka, I pick and choose; a little of most things, just to try. The wind blows strongly, flapping the edges of the tablecloth up over the dishes on the table. Hard to eat through linen. Booming in the distance makes us think it’s going to rain, but no doubt it’s the sound of cannons being fired to mark the REAL sunset and the breaking of the fast. Looks like we cheated a little. At our table are two Egyptian women who don’t speak English, but as the meal progresses, we engage them a bit with our limited Arabic; they are pleased to be able to tell us the names of some of the foods we are eating. Two Fulbright students, who I innocently observe seem to be working on similar projects, get into an increasingly tense disagreement about methodology. It’s beginning to make all of us (at least the Americans, anyway) a bit uncomfortable. I try to referee but one of the disputants talks right through me. Oh, I think, I’ve been here less than twenty-four hours and already created trouble. Great diplomatic skills. Finally, I do get in a word edgewise and suggest that everybody chill. Then apologies are offered and accepted and the meal winds down. We’re about to change the subject when one of the Fulbright office people interrupts to request that we move to another set of chairs grouped near the far end of the esplanade. A musical group, seven men and three women, has set up and are ready to play: violin, bass viol, tableh (Arab drum), qanun (zither), oud (like nothing so much as a pregnant guitar or a mandolin with a beer gut), electronic keyboard and four vocalists. For an hour and a quarter the group, Qithara Troupe, plays and sings. The leader, on the violin, is a well-known Egyptian musician who has developed a new sound which combines elements of “eastern” and “western” music. Much of the Arabic influence is still heard and generally dominates, but, as the violinist tells us in a brief interlude, he plays with major and minor chords and chromatic music to develop a new style, a fusion of many musical traditions. Indeed, at various times the music sounds like gypsy music, an Israeli folk song, a Broadway theme, a torch song, and even jazz. Interesting for that and for the fact that during the performance one hears conversations being carried on throughout the audience. Music is a social lubricant here and the etiquette is therefore different from your average big city American philharmonic event. The musicians finally stand and receive our warm applause. As they pack their instruments and quickly move off stage, their place is taken by a strikingly tall man dressed in an elaborate costume composed of knee-length black leather boots, a black shirt embroidered with white piping, black billowy trousers over which he wears a heavy ankle length skirt (also embroidered in white). Two scarves, one black, one white, are wound around his head. He is carrying a number of round, flat objects that look like tambourines. These, too carry the white on black motif .

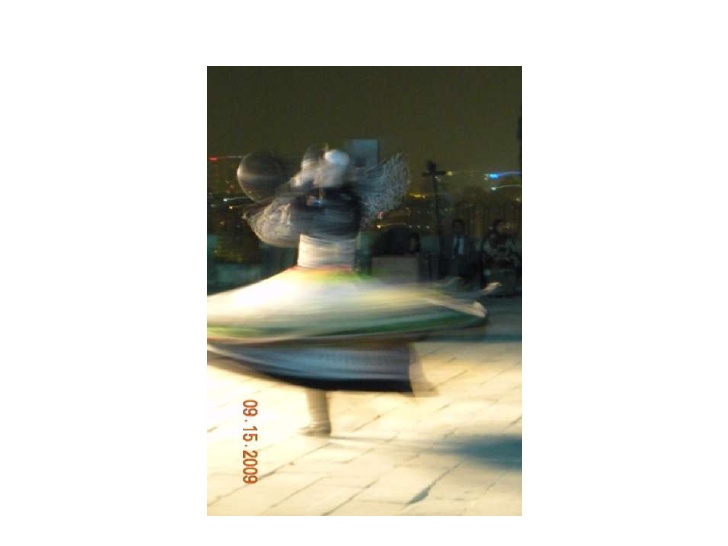

The sun is about a hand’s width above the horizon when we arrive, and we stand at a railing overlooking the Cairo skyline and the setting sun through a thick veil of smog and dust. The lights come on as we stand and talk; the wind freshens from the south and whips our hair. Along a wide esplanade paved with stone, waiters are busy laying tablecloths on tables, long ones to hold the buffet dishes and round ones where groups of six will sit and eat. The sun is still above the horizon, only barely, when we are called to the buffet line. We claim chairs for ourselves, pairing off and grouping up, and then load our plates. There are dishes that I recognize and dishes I don’t. Mezzeh, the Arabic antipasto is there: hummus (chickpeas ground finely and mixed with cumin, garlic and sesame sauce, tabbouleh (a salad made with cold cooked wheat kernels, onions, tomatoes and parsley) baba ghanoush (roasted mashed eggplant also mixed with garlic, sesame sauce and other spices), grape leaves rolled around cooked and spiced rice), kibbeh (ground lamb rolled in little sausage shapes and hiding pine nuts in the middle; these are grilled), and triangular puff pastries filled with mashed potatoes and then baked. All this is best eaten with generous amounts of pita bread—a pile of frisbee-shaped loaves sits in the middle of each table. It’s apparently traditional to begin the meal with a soup, and two are on offer. One is a vegetable soup and the other a cream type. There are rice dishes, more eggplant, a casserole that reminds me of Greek moussaka, I pick and choose; a little of most things, just to try. The wind blows strongly, flapping the edges of the tablecloth up over the dishes on the table. Hard to eat through linen. Booming in the distance makes us think it’s going to rain, but no doubt it’s the sound of cannons being fired to mark the REAL sunset and the breaking of the fast. Looks like we cheated a little. At our table are two Egyptian women who don’t speak English, but as the meal progresses, we engage them a bit with our limited Arabic; they are pleased to be able to tell us the names of some of the foods we are eating. Two Fulbright students, who I innocently observe seem to be working on similar projects, get into an increasingly tense disagreement about methodology. It’s beginning to make all of us (at least the Americans, anyway) a bit uncomfortable. I try to referee but one of the disputants talks right through me. Oh, I think, I’ve been here less than twenty-four hours and already created trouble. Great diplomatic skills. Finally, I do get in a word edgewise and suggest that everybody chill. Then apologies are offered and accepted and the meal winds down. We’re about to change the subject when one of the Fulbright office people interrupts to request that we move to another set of chairs grouped near the far end of the esplanade. A musical group, seven men and three women, has set up and are ready to play: violin, bass viol, tableh (Arab drum), qanun (zither), oud (like nothing so much as a pregnant guitar or a mandolin with a beer gut), electronic keyboard and four vocalists. For an hour and a quarter the group, Qithara Troupe, plays and sings. The leader, on the violin, is a well-known Egyptian musician who has developed a new sound which combines elements of “eastern” and “western” music. Much of the Arabic influence is still heard and generally dominates, but, as the violinist tells us in a brief interlude, he plays with major and minor chords and chromatic music to develop a new style, a fusion of many musical traditions. Indeed, at various times the music sounds like gypsy music, an Israeli folk song, a Broadway theme, a torch song, and even jazz. Interesting for that and for the fact that during the performance one hears conversations being carried on throughout the audience. Music is a social lubricant here and the etiquette is therefore different from your average big city American philharmonic event. The musicians finally stand and receive our warm applause. As they pack their instruments and quickly move off stage, their place is taken by a strikingly tall man dressed in an elaborate costume composed of knee-length black leather boots, a black shirt embroidered with white piping, black billowy trousers over which he wears a heavy ankle length skirt (also embroidered in white). Two scarves, one black, one white, are wound around his head. He is carrying a number of round, flat objects that look like tambourines. These, too carry the white on black motif .  As the dancer approaches the middle of the open space, a new sort of music blasts from two shoulder-high speakers on either side of the audience. Electronic. Disco tempo. A chest thumping bass line with a high, reed flute, snake-charming melody wailing above it. Hypnotic and insistent. The dancer—his name is Ehab El Masry—begins to move, spinning up to a constant number of revolutions per minute. His skirt flies out parallel with the ground, his feet moving heel-toe, heel-toe, heel-toe in time to the beat. The edges of the skirt show white against the black of his trousers and shirt, rippling slightly in the wind, held straight out by the force of his spinning. With his hands, he moves the tambourines to form different configurations: a line of circles running up one arm; a triangular shape held against the center of his chest; five of them, a triangle on his abdomen topped by a single column covering his neck and face; another single row stretching across his chest from fingertip to fingertip. How many tambourines does he have? I thought three, but then five and now he is holding seven. He tilts his upper body to one side and an asymmetric design running up one of his arms appears. Five minutes pass and he continues to move, changing the patterns of the tambourines again and again, never the same one twice. A change now; he deftly gathers the tambourines and deposits them on the ground in a neat pile, never breaking his movement; never losing the beat. He spins on, booted feet moving to the beat. Suddenly, the skirt is released at the waist and part of it is lifted above his head, revealing colorful stripes. The dancer lifts part of the skirt above his head so that he looks like a wildly spinning oversized psychedelic hourglass. The music pounds away. He moves again and releases one layer of the skirt from his waist, raising the bright colors above his head, twirling it like a cowboy’s lariat on one arm. He twists the garment into a barber’s pole of stripes and holds it at an angle before dropping it to the ground. Another layer of skirt is revealed and he uses this to create yet more patterns. He has been spinning now for nearly fifteen minutes; the music driving him to keep moving. The audience is riveted to this dervish version of the dance of the seven veils. Everyone has the same thought uppermost in their minds: how can he do this without falling down, puking with dizziness? With one last flourish the dance ends; the dancer halts on cue, bows and walks off from under the lights. In a straight line. Amazing. Everyone applauds enthusiastically. Our first evening together as Fulbrighters in Egypt comes to an end. We walk back through the shadows and light to the bus, are driven back to the office, and find our ways home.

As the dancer approaches the middle of the open space, a new sort of music blasts from two shoulder-high speakers on either side of the audience. Electronic. Disco tempo. A chest thumping bass line with a high, reed flute, snake-charming melody wailing above it. Hypnotic and insistent. The dancer—his name is Ehab El Masry—begins to move, spinning up to a constant number of revolutions per minute. His skirt flies out parallel with the ground, his feet moving heel-toe, heel-toe, heel-toe in time to the beat. The edges of the skirt show white against the black of his trousers and shirt, rippling slightly in the wind, held straight out by the force of his spinning. With his hands, he moves the tambourines to form different configurations: a line of circles running up one arm; a triangular shape held against the center of his chest; five of them, a triangle on his abdomen topped by a single column covering his neck and face; another single row stretching across his chest from fingertip to fingertip. How many tambourines does he have? I thought three, but then five and now he is holding seven. He tilts his upper body to one side and an asymmetric design running up one of his arms appears. Five minutes pass and he continues to move, changing the patterns of the tambourines again and again, never the same one twice. A change now; he deftly gathers the tambourines and deposits them on the ground in a neat pile, never breaking his movement; never losing the beat. He spins on, booted feet moving to the beat. Suddenly, the skirt is released at the waist and part of it is lifted above his head, revealing colorful stripes. The dancer lifts part of the skirt above his head so that he looks like a wildly spinning oversized psychedelic hourglass. The music pounds away. He moves again and releases one layer of the skirt from his waist, raising the bright colors above his head, twirling it like a cowboy’s lariat on one arm. He twists the garment into a barber’s pole of stripes and holds it at an angle before dropping it to the ground. Another layer of skirt is revealed and he uses this to create yet more patterns. He has been spinning now for nearly fifteen minutes; the music driving him to keep moving. The audience is riveted to this dervish version of the dance of the seven veils. Everyone has the same thought uppermost in their minds: how can he do this without falling down, puking with dizziness? With one last flourish the dance ends; the dancer halts on cue, bows and walks off from under the lights. In a straight line. Amazing. Everyone applauds enthusiastically. Our first evening together as Fulbrighters in Egypt comes to an end. We walk back through the shadows and light to the bus, are driven back to the office, and find our ways home.

E-Day Plus One

Wednesday, 16 September 2009

Today was business. After breakfast in the hotel (same fare; no variation) I head off for the Fulbright office two blocks away to the south (I’m getting my bearings,,,). Ranya Rashid, the office manager, arrives at almost the same time as I and smoothes my way past the guard’s station (I don’t yet have my Fulbright ID card…). In her office, we get down to the financial and logistical details of my move to Alexandria tomorrow. I’m given my medical insurance card, my Fulbright ID and sign a couple of forms. A handy backpack and baseball cap (more gifts from American taxpayers) complete my interview with her. It’s decided that because I am not going to be “working” at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina (in other words I don’t have an official “lectureship” like the Fulbrighters at AUC), I won’t need a work visa and won’t have to submit to another HIV test (looks like another good day…). Ibrahim, the man who will also be driving me to Alexandria, stops in to make arrangements for meeting tomorrow and I’m issued a cell phone for use in Egypt. I’m then escorted up to the financial officer, Fazy Attia, who hands me a check for my first two months’ stipend. We say our goodbyes I head directly off to the HSBC branch just around the corner from the Fulbright office to open my bank account. My stipend payments are henceforth to be deposited directly into that account. I ask to speak to Mai Sallam, whose name has been given me by Fazy. She hands me off to her colleague Ahmad Farid, who does the actual work. I’m asked for the usual personal information and my passport is photocopied. There’s a bit of a problem since I’ll be accessing my account from Alexandria; we have to decide which of the bank’s branches is nearest to my apartment. My ATM card is to be issued from that branch, and I don’t want to go halfway across town to get it. Well, Ahmad doesn’t know the location of the street that my apartment is on so we first ask some of Ahmad’s colleagues. No one knows. In a moment of inspiration, I suggest that Ahmad call the Fulbright office and see if someone there knows. Lines all busy. Finally, Ahmad tells me I can phone him with the information. Do I have a mobile phone number? No, not yet. A phone but no number and no minutes, but I’m on my way to get one. He says fine. Let him know the number when I have it. Will do.

Another HSBC employee stops by and starts asking me questions about Alexandria; I tell him I’ve not yet been there. He wants to know where Iowa is. He thinks it’s a state with lots of snakes. I tell him no. Just corn. The colleague offers to expedite the opening of my account and takes my check to the cashiers’ station. In five minutes he’s back to tell me that the signature on the check appears to be invalid. Great. Back to the Fulbright office, past the guard’s station (easy now, with my ID) and up to Fazy’s office. He takes the check and comes straight back with it, now bearing Ranya’s signature in addition to his. Back to the bank (the guard at the door and I are now on a first name basis by now) and the same guy with whom I dealt earlier sees me and takes the check. He asks if I want to make a withdrawal and I say yes and tell him how much. In five minutes, I have my cash and am out the door.

I set off for the Vodaphone store on Dokki Street to buy a SIM card and minutes. Locate the store, order what I want from the two young men in charge and am back out on the street in ten minutes. I hustle back to the hotel and stash the cash in the safe box in my hotel room. I feel better now. I try to call Ranya to tell her what my new number is, but she’s not answering. I call Ahmad at the bank and give him the information and then make some other phone calls to wrap things up for now.

I spend the rest of the day in the hotel using the computer and watching Egyptian television. Drivel seems to have gone viral and global. Game shows, more soaps than you can imagine (Ranya was complaining during our talk this morning that Egyptians seem to spend all of Ramadan watching this crap instead of working. I despair…) The variety of channels I find interesting. Lots of stuff in English, Spanish, German, and French. Lots of fifties-vintage Egyptian movies, too. The actor from the recent Egyptian film, The Yaacobian Building, seems to have been in nearly every Egyptian production since the early sixties. Weird watching him age forty years in a single afternoon. There’s even a glimpse of Omar Sharif, post-Dr. Zhivago.

I work at the computer for a while and after the sun has been down for a while, I head down to the ground floor and find their restaurant. The hotel brochure says there are three of them, each with a different cuisine: one Italian, one vaguely Middle Eastern, and the third a sushi restaurant, of all things. Well, why not. I sit outside on a patio raised a few feet above the street level. The young waitress who seats me can’t stop giggling once I begin to speak to her in Arabic. It’s a little unnerving when this happens (infrequently, by the way) because I never know if it’s just the unexpectedness of a westerner, specifically an American, speaking their language, or whether I’m making a complete mess of the attempt and they can’t believe someone could speak it so badly.

I order something to drink and seafood fettucine. “Frutti di mare” sounds and looks odd in Arabic: Fawakih al-bahr. Well, eating Italian food in Egypt is strange already, maybe. While I wait, I watch an older guy a couple of tables away, attired in a business suit, order a water pipe and smoke it while he drinks a soft drink from a can. Something else you wouldn’t have seen half a century ago. The drink would have been really sweet tea and the suit would have been a “galabiyah,” the floor-length shirt worn by men which one sees less and less these days.

The waitress with the laughter control problem returns to tell me that the restaurant is out of seafood, so would I like to change my order. Rats. I had my heart set on that dish. Well, I ask if they’re doing sushi still and, to my puzzlement, she says “yes.” Okay, that’s fine. Apparently they have the right kind of ocean fruit for sushi, but not for the pasta dish. Well, it’s Egypt. I get my meal and eat at a leisurely pace, watching the foot traffic on the street next to the patio. Lots of young people, particularly groups of young women in varying grades of “hijab.” Some are in jeans and heels and just covering their hair; others are dressed in long robes and have the lower halves of their faces covered, too. Couples, men and women, are rarer, but not totally absent. I even see some playful slapping and pushing going on among these last pairings, but for the most part such two-gender parties comport themselves more demurely.

Meal finished; sushi not bad, after all. I pay my bill and go off to bed. Tomorrow is moving day. I finally get to unpack.

The Librarian has landed

Tuesday 15 Sept. 2009

Thirty years since I was last here in Cairo and the city is unrecognizable, at least so far. Descending over the city in the plane, it seemed as though the lights stretched forever in all directions, although that impression could have been due to our landing pattern, circling ever lower. Long strings of street lights marked the major roads; some were long and fairly straight, others wandered in curves. Islands of lights marked areas of dense settlement in seas of relative darkness between them. As we neared the ground, it was possible to see pulsing neon in the commercial areas-restaurants, casinos, amusement areas-and green lights marking the minarets. A long narrow dark band slipped beneath us: the Nile splitting the city in two. Streams of traffic moved along the major arteries; lots of cars on the roads, it seemed.

I was met at customs by Ibrahim, the Fulbright “expediter” who took charge, showed me where to buy my visa ($15 handed to a teller in one of a row of several kiosk-style banks secured an official-looking piece of paper) which Ibrahim then handed, together with my passport, to the customs official in his booth. Once he had stamped my passport, he passed it to a woman in headscarf who was seated behind him. She appeared to enter some sort of data into a computer and then returned the passport to me. With that, we were outside in fresh air (for me the first time in 18 hrs…) and into Ibrahim’s car. It took both of us to heave my 85 lb. suitcase into the trunk… A pleasant evening for late Summer in Cairo. The air was moist, smelled of city and traffic, but not terribly hot. We set off for the Hotel Safir in a section of Cairo called “Dokki,” one of the newer suburbs in the western part of the city. I was totally disoriented until we crossed the Nile and I asked Ibrahim in which direction we were traveling. He replied, “gharbi.” West. That meant away from the Red Sea, generally; Alexandria was off to our right, north down the Nile and on the Mediterranean. The streets were full of people and cars; we had to stop several times as heavy traffic crawled to a halt and then began flowing again. I was startled to see pedestrians crossing the main streets-four or six lanes of traffic-wherever they chose. Most were invisible until we were right on top of them because they were wearing dark clothing. Glad I wasn’t driving…

It’s the holy month of Ramadan and that means that observant Muslims fast from sunup until sundown. Not an easy feat when the month falls in the long hot days of Summer. Work hours are customarily shortened during Ramadan and people tend to shift their active lives to night time. Shops and restaurants are open and doing brisk business; the many mosques are full of light, the minarets marked with green lamps along their lengths. The windows of the mosques, covered with geometric designs in masonry glow warmly in the darkness. Ibrahim points out some of the landmarks along the way: the central train station, President Mubarak’s residence, city hall. Familiar green and white street signs bear both Arabic and English place names. We turn off the main thoroughfare and down a narrower, darker, quieter side street. A neighborhood with people standing and talking with one another outside shops, drinking Coca Cola, smoking cigarettes. Ibrahim pulls up in front of the Safir Hotel, brightly lighted and marble lined. Sleek, modern, (“Recently renovated” says the marketing literature) and efficient. We lift out my suitcase, he summons a hotel employee to take it and we shake hands. “Alf shukr,” I say to him. Many thanks. We’ll see each other again in three days, when he drives me to my apartment in Alexandria. Check in. A mixture of Arabic and English spoken with the desk clerk and the “bell boy,” who is summoned to trundle my heavy bag upstairs to my room. The elevator is remarkably quiet and smooth. I hardly notice its motion at all. The bell dings and we’re on the twelfth floor. Key card inserted into the lock on the door. A quick introduction to the room’s features—TV, AC, mini-refrigerator (no booze in it…), lights. A tip to the young man in dollars (I haven’t yet had time to exchange money for Egyptian Liras) and I say good night to him, “Tisbah ala khayr.” May you awaken well. A forward-looking valedictory. A quick shower to remove the travel grime and off to a surprisingly restful sleep.

Bib Alex Blog

Watch this space for posts from Cairo and Alexandria Egypt. I will be sending periodic communiques and photos over the next four months as I participate in the Fulbright program.