Thursday, 14 January 2010

So, here I am on my way home. The first leg of three flights that will hopefully have me home and in my own bed this evening. Something like 7 AM Friday, Cairo time, but eight hours earlier in Des Moines. A long day, but my last two days in Cairo were long, too.

Tuesday, I had made two appointments to try to wrap up my block print research, at least insofar as it was possible to “wrap it up” when the largest collection—at the Museum of Islamic Art—was inaccessible. My first stop was at the Dar al-Kutub, the Egyptian Center for the Book on the Corniche downtown. I had already sent them a letter and had called them before I left Alexandria to make certain that they were expecting me. When I arrived, I told the front desk who I wanted to see and, after a bit of confusion, was ushered into Abd Allah’s office. Handshakes, smiles, an invitation to sit while he did some other business. When he returned, with a copy of my letter in hand, he told me that the director who would have to give the final okay on my seeing the artifact I wanted to see had not yet arrived. Typical.

“Okay, so I’ll come back,” I say. “I have another appointment this morning and I’ll just go there first.”

“Oh,” says Abd Allah. “What time will you come back?” Like I could possibly know. This is Egypt.

“I don’t know,” I tell him. “Could be an hour, could be an hour and a half, could be two hours.”

“Ah,” says Abd Allah, looking very unhappy.

“Sorry,” I shrug. “I have very little time left and I need to get this work done. I’ll be back.”

Climb into a cab and go off to the Egyptian Geographical Society museum next to the City Council Chambers. Always a treat having to go through security there just to get to the museum, but it’s the only way in. Dr. Abu al-Izz is expecting me, so I only have to wait fifteen minutes to be shown to his office. Dr. Abu al-Izz is eighty if he’s a day, slightly bent and rather frail, but his voice and handshake are still strong. I submit to the routine interrogation about the nature of my work and its focus, suffering his frequent interruptions with questions and comments. He is very genteel and not at all arrogant so I don’t take offence. His English is very good and I sort of like talking with him. He’s interested in what I have to say.

He finally calls in his curator (whom I met on my first visit here) and, after Dr. Abu al-Izz fills him in, the curator and I head down to the museum. Of course, the curator has his own agenda and insists on showing me a display case full of writing instruments and personal stamps that were used for indicating ownership of books and other purposes. He tells me that a group of small metal stamps was made to be carried by illiterate people who would use them instead of signing their names on government documents, contracts and the like. He tells me that such things were used until the early part of the twentieth century in Egypt. That was actually interesting.

After about half an hour of looking over the dusty stuff in that cabinet, we were brought tea and moved to the case containing the block print I came to see. The curator took the strip of paper, protected by a sheet of glass, out of the case. I took my measurements and made my observations on it. The curator tried reading it and told me that there wasn’t a single real Arabic word on the paper; it was all gibberish. I looked at it and had to admit that I didn’t see any identifiable words anywhere. If this is indeed the case, then it supports the theory that many of the block prints were not meant to be read. However, this is the first one of this kind that I have encountered.

After completing my examination, I am taken upstairs to Dr. Abu al-Izz’s office once more. I thank him for his courtesies and promise to send him a copy of my book. Since he has a block print in his collection, I say, he ought to have some reference material on them. We shake hands, promise to keep in touch and I’m off. Back at the Dart al-Kutub, I find that the director has finally arrived and I am shown into his office. The guy’s in his mid-fifties, maybe, graying kinky hair worn over his ears on the sides but thinning on top. His face is remarkably wrinkle free and open. He doesn’t tell me his name and he doesn’t speak English so, after the obligatory pleasantries, he reads through the Arabic annotations on the letter I had sent and asks me what sort of books I want to see. I tell him it’s not a book I’m interested in, but a piece of paper bearing printing. Could be from the tenth or eleventh century, maybe.

I show him the accession number and he tells me there is no such system in use in the Dar al-Kutub. Where did I get the number? I explain to him what the source is, who wrote it, and when. Not even a flicker of recognition crosses his face. Trouble, I knew it. He obviously thinks I’m an idiot because he launches into a long monologue about Arabic printing, when it started, nothing printed before such and such a date, blah, blah, blah. I let him have his say and then repeat that what I am looking for is not, repeat, NOT a book, but a document.

“It’s here? In the Dar al-Kutub?” he asks.

“As far as I know,” I reply. “The last person to have seen it, to my knowledge, saw it in the 1920’s so where exactly it might be now, I don’t have a clue.”

He thinks for a minute as people flow in and out of his office asking questions and having him review letters or documents. When he has a moment, he looks up at me and calls the head of the rare books division. He comes to the office and the director explains, as best he can, what he thinks I want. He suggests to the rare books guy that he show me what he’s got. Rare book guy and I then troop down to his office, through a warren of spaces lined with compact shelving units. Once in his office, he has his guys drag out old lithographed books for me to look at.

“Is this what you’re interested in?” How about this one?”

“Nope, and nope,” I reply shaking my head.

I recite my explanation—by now almost memorized and with much better Arabic than the first time I gave it—and he listens patiently. I describe, roughly the dimensions and what I think it looks like: three strips of paper arranged one next to the other. Each strip about 40 cm. long. He shakes his head.

“Don’t have anything like that.” “Hey Ahmad (I don’t remember his real name),” he says to one of his guys. “Do you know where such a thing might be?”

Ahmad has heard the explanation and he says, maybe in the manuscript department.

“Oh,” says the chief. “That’s a different department all together. You’ll have to go and get permission from the director’s director in order to see anything there.”

Will this never end? Back upstairs to the BIG director’s office. Of course, he’s not in and I end up sitting in his outer office with varying numbers of people, some of whom seem to be working while others seem to be hanging out and socializing. I decide that I’m not leaving until I see this guy. After an hour, Dr. Abd al-Nasser Hassan Mohamed finally shows up and I have to go through my routine again. Somewhere in all the comings and goings, my letter has disappeared and now, he says, I have no authorization to see what I want to see. I look at him and tell him that the letter is here, just track it down, please. He must decide that that would take up too much of his valuable time, so he makes a note on a photocopy of the page I’ve given him showing the accession number, and he calls one of his people to show me to the manuscripts division. I thank him and go off with the assistant to the manuscript division, down more stairs and across several bleak lobbies and staircase landings.

I enter a workroom through a door bearing the legend “Manuscript Division” in Arabic and am greeted by four young men and a hijab clad woman. I learn that they are in the process of compiling a ten-volume collection of studies on papyri that Adolf Grohmann, a famous 19th-20th century scholar, had worked on in Cairo. They know Grohmann, the source for my information about the piece I want to see. Finally, maybe some progress! When I ask if they have a copy of the book in which I found the description, they say no, but they do have a record of all his accession numbers. Unfortunately, their computer records do not show mine. Just great. But in the meantime, one of the guys asks me if the thing I’m after is on papyrus. I say no, I don’t think so.

“Too bad,” he says. “We just published a catalogue of the papyri in the National Library. Here it is.”

I start leafing through it. I notice at least two items that are clearly block prints even though the catalogue identifies them as manuscripts. The woman suddenly busies herself with some papers. The catalogue is heavily illustrated and I notice that not all the pieces are on papyrus. There are paper documents as well, and, lo and behold! here is a picture of one thing that fits the description exactly. I show the image to the guys who crowd around, murmuring among themselves. Suddenly, the woman, who has been working at an adjacent table, spins around with a set of galleys from the book I’m looking at in her hand. She points excitedly. There, in the galley, is the same page I’m looking at WITH my accession number on it. The guys quickly busy themselves with their computers. A correction is obviously in order. There was apparently an omission somewhere and that number did not get into the computer system. The woman is very excited about the discovery and I congratulate her on her keen eye. She beams. A Eureka moment.

When I ask where it is, the collective answer is, “Not here.”

My elation turns into ashes. Now what? It appears that the item IS in the Dar al-Kutub, just not in THIS one. It’s in another building known as Bab al-Khalq, located near the Museum of Islamic Art. The woman has contacted the Dr. Mohamed by phone in the meantime and he is going to notify the Bab al-Khalq that I’m coming. The director is even organizing a car to take me there. Oh, but wait. No, sorry, they close soon. You’ll have to go tomorrow, but don’t worry; they know you’re coming. I thank everyone and on my way out buy a copy of the papyri catalogue in the Dar al-Kutub bookstore.

Four hours to get to this point, and I could be annoyed, but some progress has been made, so I’ll just re-adjust my schedule for Wednesday and fit in a visit to the Dar al-Khalq. I decide that I had better take care of some other business today so that I don’t run out of time tomorrow. I grab a cab and go to Dokki to close out my Egyptian bank account. That process goes quite smoothly and I end up with a little free time before a dinner engagement, so I head to Zamalek, the island in the Nile, where I grab a cappuccino and a piece of cake at Beano’s. Another last. I walk around for a while enjoying Zamalek’s village-like atmosphere, check out some jewelry shops and handicraft stores, but am not tempted by anything.

I finally decide to call Ginger da Costa, a fellow Fulbrighter who lives nearby, to ask if I can hang out until we go to dinner. She says sure, so I traipse over to her building and spend a pleasant hour or so talking with her and her roommate Dominique. At eight, we are joined by two more Fulbrighters from upstairs and together we walk to the Trattoria, a very nice Italian restaurant where we find eight more Fulbright people waiting for us. This is a group send-off for Ginger and myself and our last chance to spend time with our friends. There is wine and good conversation. Photos are taken and hugs shared before we set off to our various abodes. Another last.

Wednesday, I was up at 6:30 and ready to go by 9. I grabbed a cab and took it to the Dar al-Kutub in Bab al-Khalq. I got there just as the place was opening. I told the guard at the entrance that I had an appointment with the director, Layla Rizk. Was she in yet? No, he tells me, not yet. May I wait? Of course. In the meantime, the guard calls the director’s office and talks with someone there. I’m guided upstairs to the office and when I explain the purpose of my visit and that the director is expecting me, he calls the director’s mobile phone and hands the receiver to me.

Dr. Rizk is on the other end. I introduce myself and tell her why I’m there. I tell her that I had been told that Dr. Mohamed at the other building had made arrangements for me to do some research here. Dr. Rizk tells me she has had no information about this. She had been at a meeting with him last night and he had mentioned nothing of this to her. I’ll have to come back. Nope, not this time. I get a little testy and tell her that I’m leaving Cairo very soon, that I’ve been trying to get access to this artifact for a month, that I am constantly given misleading or incomplete information, that I have spent more time sitting in offices and waiting than I have spent doing the research I wanted to do, etc., and I’m not happy.

“Okay,” she says. “Put my assistant on again.”

I hand the receiver to the guy who says “Hello,” and then “Yes, ma’am, yes, ma’am.”

I’m then escorted downstairs to another office where I meet an assistant director who listens to my request and, with assistance from her colleague, starts looking for my accession number. Same story as yesterday. They don’t have it. I ask if they have a library or a bookstore in the building. Yes they do. May I see it? Of course. There is a copy of the catalogue there and I get permission to take the book to the assistant director’s office where I show her what I want to see.

“Oh, that!” she says. “That’s upstairs in conservation. I’ll get someone to take you up.”

Hallelujah! I finally get to see what I came to see and am treated very nicely the entire time. I promise to send a copy of my book to the assistant director for their library and thank her for all her help.

I go out and hop another cab to the Gayer-Anderson Museum where I’m also expected. Now that I’m known there, the director greets me like a long-lost friend and within half an hour I am in the archives, searching—with the assistance of two women employees of the museum–for my missing block print. Two drawers and umpteen conservation folders later, we finally find the last of the four block prints that I had been told were here. A very nice one, small, but very clearly printed. I do my work, say thanks and goodbye to the director and his staff and take a deep breath. I’m officially done with the research part of my project. And not a minute to spare.

Later that afternoon, I head to Dokki again to say goodbye to Bruce Lohof and his staff at the Fulbright office. Bruce and I spend an hour in very pleasant and lively conversation. I tell him how much I admire his operation and thank him, again, for the opportunity to participate in his program. I head back home to change for dinner and stop in briefly at Zohair Hussain’s apartment around the corner to say goodbye to him. He has guests and insists on feeding me before I leave, despite my protestations that I’m already invited to eat. I offer my apologies for having to run off and we give each other a hug at the door. I’ll miss his intensity. My last evening in Cairo is spent at Jamie Balfour-Paul’s houseboat apartment where Ginger, Dominique and I enjoy a home cooked meal and a couple bottles of wine. Jamie is a wonderful host and the food is good and filling. Fruit salad and blue cheese and crackers top it all off. At ten, I say my final goodbyes and take a cab home. At midnight I’m in bed; in six hours, I’ll be on my way to the Cairo airport.

Ibrahim picked me up this morning and with light morning traffic, I was through security and re-packing my way-too-heavy suitcase. I had to remove a bunch of stuff and pack it in a cardboard box (which they provided) so that my heavy case wouldn’t break the conveyor in Heathrow (so I’m told). After that, things went quite smoothly. Cairo slid away from under us in the early morning sun. The Nile, Saladin’s Citadel, Muhammad Ali’s mosque and other landmarks I knew from my stay were soon out of sight. The snowy Alps passed under us a while ago and we’re now descending into Heathrow. Time to close this operation down. I’m going home.

Vendors still cry their wares in the streets, “Eggs!” “Clean water!” “Propane!” Subsidized bread is sold on the streets, one Egyptian pound for five or six pitas, so that the poorest will have something, at least, to feed their families. On the other hand, shopping malls the equal of any found in the States or Europe are everywhere, and tennagers are hanging out just like in the States. One of the dismaying aspects of modern Egyptian life is that it is creating a generation of mall rats, just like us.

Vendors still cry their wares in the streets, “Eggs!” “Clean water!” “Propane!” Subsidized bread is sold on the streets, one Egyptian pound for five or six pitas, so that the poorest will have something, at least, to feed their families. On the other hand, shopping malls the equal of any found in the States or Europe are everywhere, and tennagers are hanging out just like in the States. One of the dismaying aspects of modern Egyptian life is that it is creating a generation of mall rats, just like us.

Internationally recognized scholars and professionals were educated, live and work here, but the ability to read is limited to about two-thirds of the population. Libraries are still relatively rare, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina notwithstanding, and while booksellers stalls are not uncommon, few Egyptian homes have bookshelves. Men sitting in cafes drinking coffee and sucking on water pipes rarely seem to have their noses in newspapers or magazines as Americans or Europeans would. At the same time, the seams of the universities are bursting from the huge numbers of students attending classes and I have to assume that they are reading. The street adjacent to the University of Alexandria’s Business and Tourism campus has at least four bookstores which carry textbooks as well as more mainstream fare, and they seem to be bustling, or at least not going out of business any time soon. On any given day, the Alexandria Library, which can accommodate two thousand readers, is at least half full of people studying. But books are expensive and the poor probably have better things to do with their money.

Internationally recognized scholars and professionals were educated, live and work here, but the ability to read is limited to about two-thirds of the population. Libraries are still relatively rare, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina notwithstanding, and while booksellers stalls are not uncommon, few Egyptian homes have bookshelves. Men sitting in cafes drinking coffee and sucking on water pipes rarely seem to have their noses in newspapers or magazines as Americans or Europeans would. At the same time, the seams of the universities are bursting from the huge numbers of students attending classes and I have to assume that they are reading. The street adjacent to the University of Alexandria’s Business and Tourism campus has at least four bookstores which carry textbooks as well as more mainstream fare, and they seem to be bustling, or at least not going out of business any time soon. On any given day, the Alexandria Library, which can accommodate two thousand readers, is at least half full of people studying. But books are expensive and the poor probably have better things to do with their money. I buy the tastiest little bananas from a guy on a corner between my apartment and the Muzak-filled San Stefano Mall, which even featured a two-story live Christmas tree in the central hub earlier this year. I prefer his fruit but, because of the concern for hygiene, I don’t buy root vegetables from him. I can find veggies wrapped in plastic in the local mall, just like in the States and those Egyptians who want to be “modern” buy theirs there, too. My banana man’s days are numbered, I’m afraid. What will happen when he loses his livelihood? More fodder for the Islamists who blame all this change on “westerners?”

I buy the tastiest little bananas from a guy on a corner between my apartment and the Muzak-filled San Stefano Mall, which even featured a two-story live Christmas tree in the central hub earlier this year. I prefer his fruit but, because of the concern for hygiene, I don’t buy root vegetables from him. I can find veggies wrapped in plastic in the local mall, just like in the States and those Egyptians who want to be “modern” buy theirs there, too. My banana man’s days are numbered, I’m afraid. What will happen when he loses his livelihood? More fodder for the Islamists who blame all this change on “westerners?” Many, if not most, small farmers in Egypt still farm with draft animals, donkeys, horses, and “tuktuks,” the water buffalo one sees in fields all along the Nile. Tractors are here and there, but they are still a relative rarity, except in the larger farming villages. In the meantime, industrial farming is making inroads. I’m told that virtually all the milk consumed in Egypt comes from one dairy. Okay, so the Egyptians aren’t big milk drinkers, but even so.

Many, if not most, small farmers in Egypt still farm with draft animals, donkeys, horses, and “tuktuks,” the water buffalo one sees in fields all along the Nile. Tractors are here and there, but they are still a relative rarity, except in the larger farming villages. In the meantime, industrial farming is making inroads. I’m told that virtually all the milk consumed in Egypt comes from one dairy. Okay, so the Egyptians aren’t big milk drinkers, but even so. Once our group had gathered, we re-boarded the bus and left the Valley of the Kings. On the way out, Omar pointed out the house built by Howard Carter, the excavator of King Tut’s tomb and one of the early archaeologists of pharaonic Egypt. There is a plan to turn the building into a museum, but at present it is not open. We had to satisfy ourselves with a view from a distance. Our next stop was the Valley of the Queens where we made a similar tour with similar restrictions. The most famous tomb here, that of Nefertiti, has been closed for years due to the fragility of its art. There are plans (Egypt always has plans…) to reopen it, but it seems that every time the authorities decide that they have a way to minimize the deleterious effects of thousands of visitors, another obstacle presents itself. In truth one wonders how it is possible to both preserve and make accessible historical sites such as these. Perhaps it isn’t. We may go down in history as the ones responsible for destroying in three hundred years what had lasted for four thousand. What a sad legacy that would be.

Once our group had gathered, we re-boarded the bus and left the Valley of the Kings. On the way out, Omar pointed out the house built by Howard Carter, the excavator of King Tut’s tomb and one of the early archaeologists of pharaonic Egypt. There is a plan to turn the building into a museum, but at present it is not open. We had to satisfy ourselves with a view from a distance. Our next stop was the Valley of the Queens where we made a similar tour with similar restrictions. The most famous tomb here, that of Nefertiti, has been closed for years due to the fragility of its art. There are plans (Egypt always has plans…) to reopen it, but it seems that every time the authorities decide that they have a way to minimize the deleterious effects of thousands of visitors, another obstacle presents itself. In truth one wonders how it is possible to both preserve and make accessible historical sites such as these. Perhaps it isn’t. We may go down in history as the ones responsible for destroying in three hundred years what had lasted for four thousand. What a sad legacy that would be. Our final stop was the temple at Memnon, famous for being all that remains of the largest temple complex of the ancient world, larger even than Karnak (which is the largest surviving temple complex). The two statues depict Amenhotep III, who ruled as a “god-king” about 1400 BC. The statues were heavily damaged by the 27 BC earthquake that did extensive damage to ancient Egypt. In later years, this area was subjected to frequent flooding making the temple site unusable, but the statues have remained. For 3400 years. The ravages of time on the colossi are quite evident but there is still an impression of grandeur and gravity about them. Interestingly, the stone for one of the statues was transported from a place near present-day Cairo, rather than from Aswan as the stone work for so many other ancient Egyptian temples and statues was. And because of its size—some 700 tons(!)—it was transported overland, not by river barge… Were these people nuts?

Our final stop was the temple at Memnon, famous for being all that remains of the largest temple complex of the ancient world, larger even than Karnak (which is the largest surviving temple complex). The two statues depict Amenhotep III, who ruled as a “god-king” about 1400 BC. The statues were heavily damaged by the 27 BC earthquake that did extensive damage to ancient Egypt. In later years, this area was subjected to frequent flooding making the temple site unusable, but the statues have remained. For 3400 years. The ravages of time on the colossi are quite evident but there is still an impression of grandeur and gravity about them. Interestingly, the stone for one of the statues was transported from a place near present-day Cairo, rather than from Aswan as the stone work for so many other ancient Egyptian temples and statues was. And because of its size—some 700 tons(!)—it was transported overland, not by river barge… Were these people nuts?

One such was a “dahabiyah,” all white, being towed by a small, similarly painted tugboat. This was the sort of conveyance that our friend Flo Nightingale would have made her trip in—minus the tugboat. I wondered how much different an experience that must have been. It looked to be a comfortable enough boat, but she reports that in addition to her three traveling companions, there were numerous crew members responsible for sailing or rowing or towing the boat along. It must have been quite cozy and her less than affectionate references to the companionship of various rodent and insect life forms made me appreciative of the comforts of our ship.

One such was a “dahabiyah,” all white, being towed by a small, similarly painted tugboat. This was the sort of conveyance that our friend Flo Nightingale would have made her trip in—minus the tugboat. I wondered how much different an experience that must have been. It looked to be a comfortable enough boat, but she reports that in addition to her three traveling companions, there were numerous crew members responsible for sailing or rowing or towing the boat along. It must have been quite cozy and her less than affectionate references to the companionship of various rodent and insect life forms made me appreciative of the comforts of our ship.

Around noon, the landscape underwent a dramatic change; through the haze—which was surprising as much for its presence as for its heaviness—we saw a range of reddish mountains looming on the east bank. Here the Nile made a grand sweep to the west as it sought a way around this impediment to its progress. At times the mountains seemed close enough to touch, appearing right behind the narrow strip of green that bordered the river. Soon the mountains receded, however and we continued our float, taking in the landscape and relaxing. We spent a great deal of the morning topside alternately reading and taking in the view of the landscape. Everyday activities were being carried out in the small settlements we passed along the way. I had the sense that what we viewed as a bucolic environment had quite a different meaning for those who were scratching out a living and dependent on the river for their existence in a manner totally different from the cruise boat operators. Draft animals were everywhere; women did their laundry at the river’s edge, as countless generations of women before them had no doubt done. Children in hand-me-down galabiyahs herded animals or ran through the fields, some waving as we passed; others, apparently long since inured to sight of wealthy foreigners staring at them, went about their business without so much as a glance our way.

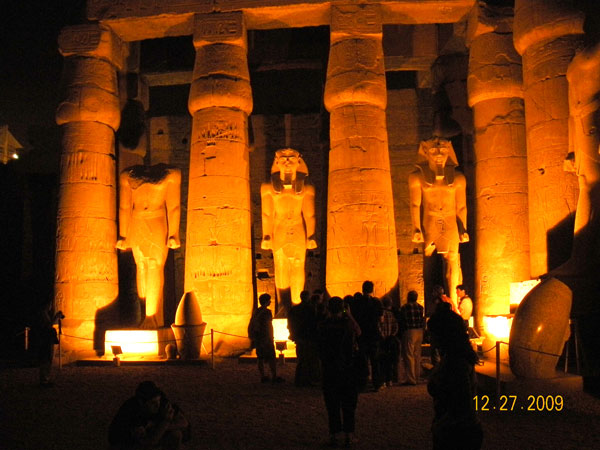

Around noon, the landscape underwent a dramatic change; through the haze—which was surprising as much for its presence as for its heaviness—we saw a range of reddish mountains looming on the east bank. Here the Nile made a grand sweep to the west as it sought a way around this impediment to its progress. At times the mountains seemed close enough to touch, appearing right behind the narrow strip of green that bordered the river. Soon the mountains receded, however and we continued our float, taking in the landscape and relaxing. We spent a great deal of the morning topside alternately reading and taking in the view of the landscape. Everyday activities were being carried out in the small settlements we passed along the way. I had the sense that what we viewed as a bucolic environment had quite a different meaning for those who were scratching out a living and dependent on the river for their existence in a manner totally different from the cruise boat operators. Draft animals were everywhere; women did their laundry at the river’s edge, as countless generations of women before them had no doubt done. Children in hand-me-down galabiyahs herded animals or ran through the fields, some waving as we passed; others, apparently long since inured to sight of wealthy foreigners staring at them, went about their business without so much as a glance our way. In late afternoon, Luxor hove into view and we tied up at the Eastmar dock, some distance south of the city proper. After the ship was secured, we all trooped aboard a bus and set off for the famous Temple of Karnak. This temple stood and was active for over a thousand years. It is the largest pharaonic temple complex in Egypt. Numerous Pharaohs and their Greek and Roman successors renovated, rebuilt and expanded its precincts over time so that one sees a number of different architectural styles. The most spectacular element is the colonnaded hall of the main temple. The massive pillars are carved to resemble lotus plants, the capitals curving out gracefully at the top. The entire complex covers at least ten acres and includes a “sacred lake” where priests would ritually cleanse themselves before entering the inner sanctum. There’s an obelisk, too, one of two that originally stood here, their pyramidal tops sheathed in a mixture of gold and silver that brilliantly reflected the sun’s rays in honor of the sun god worshipped in this place. One of the obelisks was toppled and the second walled up out of spite and ironically preserved for us because of one ruler’s jealousy of a predecessor. Funny, how history works…

In late afternoon, Luxor hove into view and we tied up at the Eastmar dock, some distance south of the city proper. After the ship was secured, we all trooped aboard a bus and set off for the famous Temple of Karnak. This temple stood and was active for over a thousand years. It is the largest pharaonic temple complex in Egypt. Numerous Pharaohs and their Greek and Roman successors renovated, rebuilt and expanded its precincts over time so that one sees a number of different architectural styles. The most spectacular element is the colonnaded hall of the main temple. The massive pillars are carved to resemble lotus plants, the capitals curving out gracefully at the top. The entire complex covers at least ten acres and includes a “sacred lake” where priests would ritually cleanse themselves before entering the inner sanctum. There’s an obelisk, too, one of two that originally stood here, their pyramidal tops sheathed in a mixture of gold and silver that brilliantly reflected the sun’s rays in honor of the sun god worshipped in this place. One of the obelisks was toppled and the second walled up out of spite and ironically preserved for us because of one ruler’s jealousy of a predecessor. Funny, how history works…

We went to dinner at the famous Fish Market restaurant one evening and had a memorable feast followed by the best Arabic coffee I’ve ever drunk. Another day my Arabic tutor took us to al-Muntaza, the site of King Farouk’s summer palace, where we walked part of the extensive gardens along the seacoast and returned to downtown Alexandria for yet another meal of fish.

We went to dinner at the famous Fish Market restaurant one evening and had a memorable feast followed by the best Arabic coffee I’ve ever drunk. Another day my Arabic tutor took us to al-Muntaza, the site of King Farouk’s summer palace, where we walked part of the extensive gardens along the seacoast and returned to downtown Alexandria for yet another meal of fish. Last Thursday, we boarded a train for Cairo, spent Christmas Eve in an airport hotel, and then took an early morning flight to Aswan, the last major city in southern Egypt before you reach the Sudanese border (still another five hundred miles farther south) and the site of the famous high dam built under Nasser. In Aswan, we boarded the cruise ship “Ra II,” and began our four day trip down the Nile (that is, North) to Luxor. This is a very touristy thing to do and, next to the obligatory visit to the pyramids at Giza, probably the most quintessential Egyptian experience for non-Egyptians.

Last Thursday, we boarded a train for Cairo, spent Christmas Eve in an airport hotel, and then took an early morning flight to Aswan, the last major city in southern Egypt before you reach the Sudanese border (still another five hundred miles farther south) and the site of the famous high dam built under Nasser. In Aswan, we boarded the cruise ship “Ra II,” and began our four day trip down the Nile (that is, North) to Luxor. This is a very touristy thing to do and, next to the obligatory visit to the pyramids at Giza, probably the most quintessential Egyptian experience for non-Egyptians.

The Ptolemies had a policy of currying favor with the native Egyptians by honoring the gods that they worshipped and even building temples in their honor. The Temple at Philae is one such building, dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis, to whom the island of Philae was sacred.

The Ptolemies had a policy of currying favor with the native Egyptians by honoring the gods that they worshipped and even building temples in their honor. The Temple at Philae is one such building, dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis, to whom the island of Philae was sacred.

We spent a very pleasant couple of hours wandering around the site in the early morning cool, taking pictures and trying to make sense of the hieroglyphics and pictures that adorn the walls of the larger structures that make up this temple complex. The Romans followed the Greek practice of showing respect to the ancient Egyptian deities and added their own buildings to the assemblage.

We spent a very pleasant couple of hours wandering around the site in the early morning cool, taking pictures and trying to make sense of the hieroglyphics and pictures that adorn the walls of the larger structures that make up this temple complex. The Romans followed the Greek practice of showing respect to the ancient Egyptian deities and added their own buildings to the assemblage.  Thus, you have a range of architectural styles and traditions within a relatively small area and another example of the sort of syncretism that so deeply characterizes the culture of this part of the world.

Thus, you have a range of architectural styles and traditions within a relatively small area and another example of the sort of syncretism that so deeply characterizes the culture of this part of the world.

To the rest of us, he is best known as Rita Hayworth’s father-in-law. The tomb lies across from Gazirat al-Bustan, the garden island, where we now disembarked. The gardens are home to variety of trees and shrubs collected and planted by Lord Kitchener. Now quite mature, the plantings create a very elegant colonial specimen garden on the northern part of the island. It was most pleasant to spend an hour or so amidst the shade of palms and tamarinds, among the colors of bougainvillea, hibiscus and other flowering plants. At the end of our visit, a motor boat took us around the southern tip of Elephantine Island and back to our ship’s berth.

To the rest of us, he is best known as Rita Hayworth’s father-in-law. The tomb lies across from Gazirat al-Bustan, the garden island, where we now disembarked. The gardens are home to variety of trees and shrubs collected and planted by Lord Kitchener. Now quite mature, the plantings create a very elegant colonial specimen garden on the northern part of the island. It was most pleasant to spend an hour or so amidst the shade of palms and tamarinds, among the colors of bougainvillea, hibiscus and other flowering plants. At the end of our visit, a motor boat took us around the southern tip of Elephantine Island and back to our ship’s berth.

We returned to the ship in time for lunch and, while we were eating, we set sail for our next stop, Kom Ombo, a temple sitting right on the east bank of the Nile about forty miles north of Aswan. The ship’s progress was sedate and watching the river slide past under the afternoon sun was a delightful, even serene, experience. The importance of the narrow strip of green running alongside the Nile through desert becomes much clearer when seen from the deck of a Nile liner. The cultivated area is limited to the narrow flood plain adjacent to the river and the proximity of the arid lands is emphasized by the high sand-covered bluffs beyond. It is somewhat of a surprise that human habitation seems to be ever present here, but when one considers that there is no place far from the river where human life can be sustained, it makes sense that everywhere the banks allow for cultivation, people will be found.

We returned to the ship in time for lunch and, while we were eating, we set sail for our next stop, Kom Ombo, a temple sitting right on the east bank of the Nile about forty miles north of Aswan. The ship’s progress was sedate and watching the river slide past under the afternoon sun was a delightful, even serene, experience. The importance of the narrow strip of green running alongside the Nile through desert becomes much clearer when seen from the deck of a Nile liner. The cultivated area is limited to the narrow flood plain adjacent to the river and the proximity of the arid lands is emphasized by the high sand-covered bluffs beyond. It is somewhat of a surprise that human habitation seems to be ever present here, but when one considers that there is no place far from the river where human life can be sustained, it makes sense that everywhere the banks allow for cultivation, people will be found.

As we rode along a two-lane road bordered by a canal on one side and rows of palm trees standing in narrow fields on the other, she spoke of the duality that the ancient Egyptians saw in existence: that humans were animated by two forces, the “Ka” and the “Ba,” the soul and something like a “motive force.” A person needed both forces in order to exist on this plane. When one dies, the Egyptians believed, the Ka departs for the sky where it is judged. If it passes judgment, then it is rewarded with eternal life; if it does not pass, it is drowned in a celestial sea and is really dead. It is this second death that the Egyptians feared more than the first. If a soul (Ka) survived the judgment of the gods, then it could be reunited with its Ba again on Earth, but in order for that to happen, the Ka had to have a “home” to return to, where it could be reunited with its Ba. That was the reason for mummification and for the elaborate measures taken by the Pharaohs to assure that their bodies would survive until the resurrection. There was much more than that to the story: the one omnipotent god Amen, two sons, one good, one evil, the myth of creation, and so forth that were clearly the antecedents of the biblical stories with which we are familiar, but this should give you an idea of the basic elements of that world view.

As we rode along a two-lane road bordered by a canal on one side and rows of palm trees standing in narrow fields on the other, she spoke of the duality that the ancient Egyptians saw in existence: that humans were animated by two forces, the “Ka” and the “Ba,” the soul and something like a “motive force.” A person needed both forces in order to exist on this plane. When one dies, the Egyptians believed, the Ka departs for the sky where it is judged. If it passes judgment, then it is rewarded with eternal life; if it does not pass, it is drowned in a celestial sea and is really dead. It is this second death that the Egyptians feared more than the first. If a soul (Ka) survived the judgment of the gods, then it could be reunited with its Ba again on Earth, but in order for that to happen, the Ka had to have a “home” to return to, where it could be reunited with its Ba. That was the reason for mummification and for the elaborate measures taken by the Pharaohs to assure that their bodies would survive until the resurrection. There was much more than that to the story: the one omnipotent god Amen, two sons, one good, one evil, the myth of creation, and so forth that were clearly the antecedents of the biblical stories with which we are familiar, but this should give you an idea of the basic elements of that world view.

On a wide rock shelf stood an empty sarcophagus, the lid pushed back so that one could peer in. The corpse of the deceased had long since disappeared, but there was no way to get that great stone box out except in pieces. After a short look around, the group re-emerged under its own power, unlike the original inhabitant.

On a wide rock shelf stood an empty sarcophagus, the lid pushed back so that one could peer in. The corpse of the deceased had long since disappeared, but there was no way to get that great stone box out except in pieces. After a short look around, the group re-emerged under its own power, unlike the original inhabitant.

As with the other pyramids, there was a temple complex connected to this one. An architectural advisor to the archaeologist who worked here in the 1920’s found stones from the enclosure wall under the sands and restored part of it, together with a colonnade of forty-two pillars carved to resemble bundles of reeds. There is also a ceremonial ground with the remains of two raised platforms. It was here that the Pharaoh, after a reign of thirty years, had to perform a ritual called the “Heb Sed,” during which he had to run seven times around a circuit about an eighth of a mile in length in order to prove his fitness to continue governing. I wondered how old Teti, who is reputed to have lived to the age of 94, managed that. Maybe there was no time limit…

As with the other pyramids, there was a temple complex connected to this one. An architectural advisor to the archaeologist who worked here in the 1920’s found stones from the enclosure wall under the sands and restored part of it, together with a colonnade of forty-two pillars carved to resemble bundles of reeds. There is also a ceremonial ground with the remains of two raised platforms. It was here that the Pharaoh, after a reign of thirty years, had to perform a ritual called the “Heb Sed,” during which he had to run seven times around a circuit about an eighth of a mile in length in order to prove his fitness to continue governing. I wondered how old Teti, who is reputed to have lived to the age of 94, managed that. Maybe there was no time limit…

The interior of this pyramid was accessible to the adventurous so those wanting to see the inside climbed a crude staircase to a point about halfway up the north face and entered yet another tight fitting sloping passageway. One crabs along for about 150 feet to the first of two chambers at the base of the pyramid—if one wants to. I got about halfway down and was overwhelmed by the humidity and rather unpleasant odors wafting up from below, so I retreated. Seen one claustrophobia-inducing space, seen them all. Those intrepid souls who made it down and back emerged gasping for air and complaining of the noxious odors that greeted them in the basement. In true Egyptian fashion, there was a ventilating unit parked at an angle next to the entry, but it wasn’t connected to any electrical source and obviously hadn’t worked in some time. From our perch next to the entryway on the pyramid, we could see at least ten other pyramids dotting the landscape, all the way to Giza.

The interior of this pyramid was accessible to the adventurous so those wanting to see the inside climbed a crude staircase to a point about halfway up the north face and entered yet another tight fitting sloping passageway. One crabs along for about 150 feet to the first of two chambers at the base of the pyramid—if one wants to. I got about halfway down and was overwhelmed by the humidity and rather unpleasant odors wafting up from below, so I retreated. Seen one claustrophobia-inducing space, seen them all. Those intrepid souls who made it down and back emerged gasping for air and complaining of the noxious odors that greeted them in the basement. In true Egyptian fashion, there was a ventilating unit parked at an angle next to the entry, but it wasn’t connected to any electrical source and obviously hadn’t worked in some time. From our perch next to the entryway on the pyramid, we could see at least ten other pyramids dotting the landscape, all the way to Giza.

Oh, THERE it is, complete with brass plaque identifying it. Right around the corner from Ginger’s apartment, to her surprise. We thank the guard and I head back to the apartment to put my feet up. I spend rest of the afternoon catching up on blog entries and editing the collection development policy statements which are beginning to trickle in from the selectors at the Bibliotheca. By 6:30, Belle hasn’t shown up so I decide to walk across the river and try the restaurant that Ginger and I had seen earlier in the day. I eat a middling meal of eggplant moussaka amid couples chatting over their own meals and smoking to excess.

Oh, THERE it is, complete with brass plaque identifying it. Right around the corner from Ginger’s apartment, to her surprise. We thank the guard and I head back to the apartment to put my feet up. I spend rest of the afternoon catching up on blog entries and editing the collection development policy statements which are beginning to trickle in from the selectors at the Bibliotheca. By 6:30, Belle hasn’t shown up so I decide to walk across the river and try the restaurant that Ginger and I had seen earlier in the day. I eat a middling meal of eggplant moussaka amid couples chatting over their own meals and smoking to excess. Wednesday morning comes too soon. I haven’t slept well and have to drag myself up. Belle is already in the kitchen finishing her breakfast as I come in to make some tea. I had offered to treat her to dinner in gratitude for her hospitality, and we decide to meet this evening. She heads off and I start getting ready for the first day of the workshop. I had made use of the washing machine the day before and now had clothing free of desert dust, but I still needed to iron a shirt. I took care of that and then dressed and grabbed a cab for Zamalek.

Wednesday morning comes too soon. I haven’t slept well and have to drag myself up. Belle is already in the kitchen finishing her breakfast as I come in to make some tea. I had offered to treat her to dinner in gratitude for her hospitality, and we decide to meet this evening. She heads off and I start getting ready for the first day of the workshop. I had made use of the washing machine the day before and now had clothing free of desert dust, but I still needed to iron a shirt. I took care of that and then dressed and grabbed a cab for Zamalek.